Brief Notes on Kasy and Sautmann's Exploration Sampling

I’ve been spending a fair bit of time digging through the literature on the cognitive science of learning and one consistent result from the literature is that taking notes (ideally good notes) is really helpful for making sure that you learn and remember something. I typically take quick notes in Zotero when I read papers or books but when I go back to the notes a month or two later often find that they aren’t that useful. For the next month or so, I’m going to instead share quick notes on stuff I’ve read through blog posts to see if that is a more effective way of making sure I don’t forget everything I’ve read.

In the first post in this series, I discuss Kasy and Sautmann’s paper “Adaptive Treatment Assignment in Experiments for Policy.” In their paper, Kasy and Sautmann analyze treatment assignment rules for experiments with adaptive treatment assignments and come up with a new adaptive treatment assignment rule, which they call “exploration sampling,” which performs a lot better the most commonly used rule in some contexts. That’s a lot of jargon for one sentence so let me elaborate on each of those points.

Adaptive Treatment Assignment

“Adaptive treatment assignment” refers to the practice of adjusting the probability of treatment assignment over the course of an experiment. In a typical experiment, all study participants are assigned all at once to one of several treatment arms (or a control) at the start of the study. This practice works fine if you are just comparing one treatment to a control but isn’t really optimal if you are trying to compare several different treatments and are able to observe study outcomes relatively quickly. For example, let’s say you are running an experiment with 10 different treatment arms and notice halfway through that 5 of the arms are doing well and 5 are doing really poorly. Intuitively, it seems like it would make sense to drop the 5 that are doing really poorly and distribute the remaining sample between the 5 that are doing really well.

Thompson Sampling

The most commonly used approach to adaptive treatment assignment is Thompson sampling. With Thompson sampling, study participants are randomly assigned to each arm one at a time according to the posterior probability that that arm is the best. For example, let’s say you are in the situation described above and halfway through a study comparing 10 different treatment arms you estimate that there is a 15% probability that each of the first 5 treatment arms is the best and a 5% probability that each of the remaining arms is the best you would assign the next study participant to each of the first 5 arms with 15% probability and to each of the next 5 arms with 5% probability.

Thompson Sampling Works Well In Sample but Not Out of Sample

Thompson sampling works reasonably well when your goal is to maximize the welfare of the study participants. If that is your goal, you face a classic “exploration-exploitation” tradeoff – i.e. when randomly assigning a study participant you must weigh the benefit of exploring the treatment space by assigning the participant to a treatment arm that looks less effective but which could be more effective than your current best bet and exploiting your current information by assigning the participant to your current best bet. There are a lot of contexts where maximizing the welfare of study participants is more of less your real goal and Thompson sampling works great. [ russo et al ] provide a lot of great examples (and also a great more detailed intro to Thompson sampling). There are a lot of contexts where this isn’t really your goal though and, to a first approximation, you don’t really care about the welfare of the study participants. Bio-ethicists would probably disagree, but I think that the recent COVID-19 vaccine and therapeutic trials (at least two of which used adaptive treatment assignment btw) are good examples of this. These trials were conducted on relatively small samples of healthy young adults with the goal of identifying the best vaccine/treatments for COVID-19 for pretty much the entire population of the world. With those trials, you care far more about selecting the best treatments than about whether the study participants themselves were assigned the best treatment. Thompson sampling doesn’t work great in those contexts because it assigns far too large a share of study participants to the treatment arm that appears the best rather than exploring other potential arms.

Exploration Sampling for Policy Selection

In theory, given any specific experiment and the objective of selecting the treatment arm at the end of the experiment, you could figure out an optimal treatment assignment strategy using dynamic stochastic programming. The basic idea behind this technique is that you map out each and every possible treatment assignment and outcome over time kind of like if you were trying to find the optimal strategy for chess by mapping out each potential move and response. This quickly becomes computationally infeasible though.

Kasy and Sautmann’s contribution is to define a general rule for treatment assignment which seems to do much better than Thompson sampling when the goal of an experiment is to select the best treatment arm. They call their rule “exploration sampling” (to emphasize the lack of a exploitation motive) and it is really simple. Rather than assigning units to treatment arm d according to the posterior probability at time t that arm d is the best arm (\(p^d_t\)) as in Thompson sampling you instead assign participants with probability:

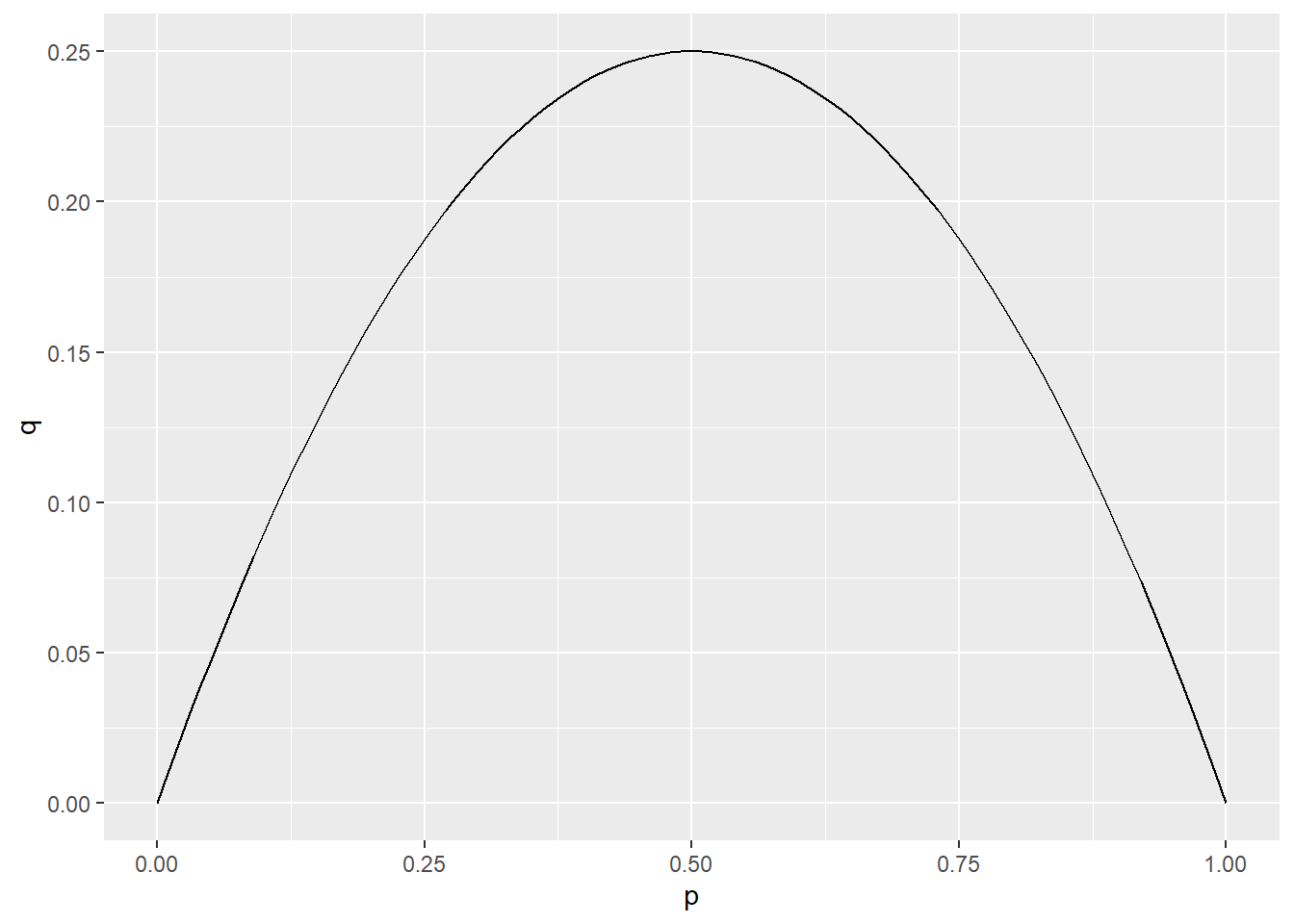

\[ q^d_t = \frac{p^d_t*(1-p^d_t)}{\sum_d{p^d_t*(1-p^d_t)}} \]

The graph below shows how q varies with p. Unlike with Thompson sampling, once a treatment arm appears to be the best (i.e. p > .5), treatment assignment probability gradually goes does to give space to learn about other treatment arms.

library(ggplot2)

ggplot() + xlim(0, 1) +

geom_function(fun = function(x) x*(1-x)) +

labs(x = "p", y = "q") The other slight difference between exploration sampling and Thompson sampling is that they allow for treatment assignment in batches. Their motivation here is logistical rather than statistical – in most RCTs it would be extremely challenging to randomly assign individual units to arms.

The other slight difference between exploration sampling and Thompson sampling is that they allow for treatment assignment in batches. Their motivation here is logistical rather than statistical – in most RCTs it would be extremely challenging to randomly assign individual units to arms.

Results from a Simulation

In addition to showing that exploration sampling has nice theoretical properties, they show that it seems to work well in practice by comparing the performance of regular one-off treatment asssignment, Thompson sampling, and exploration sampling using a Monte Carlo simulation in which the data generating process is based on the estimated parameters for a few well known multi-arm RCTs.