Multiple Hypothesis Testing

This week, I volunteered to read and summarize one of the articles for IDinsigh’s tech team’s book club. The topic for this week is multiple hypothesis testing and the article I volunteered to summarize is “Multiple Inference and Gender Differences in the Effects of Early Intervention: A Reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Training Projects” by Michael Anderson. You can find an ungated version of the article here.

Since not everyone at IDinsight has time to participate in these calls and I tend to forget anything that I don’t write down I thought I’d do a blog post on the article. I’m not going to summarize the article itself, but rather just the key takeaways.

The problem with multiple hypothesis testing

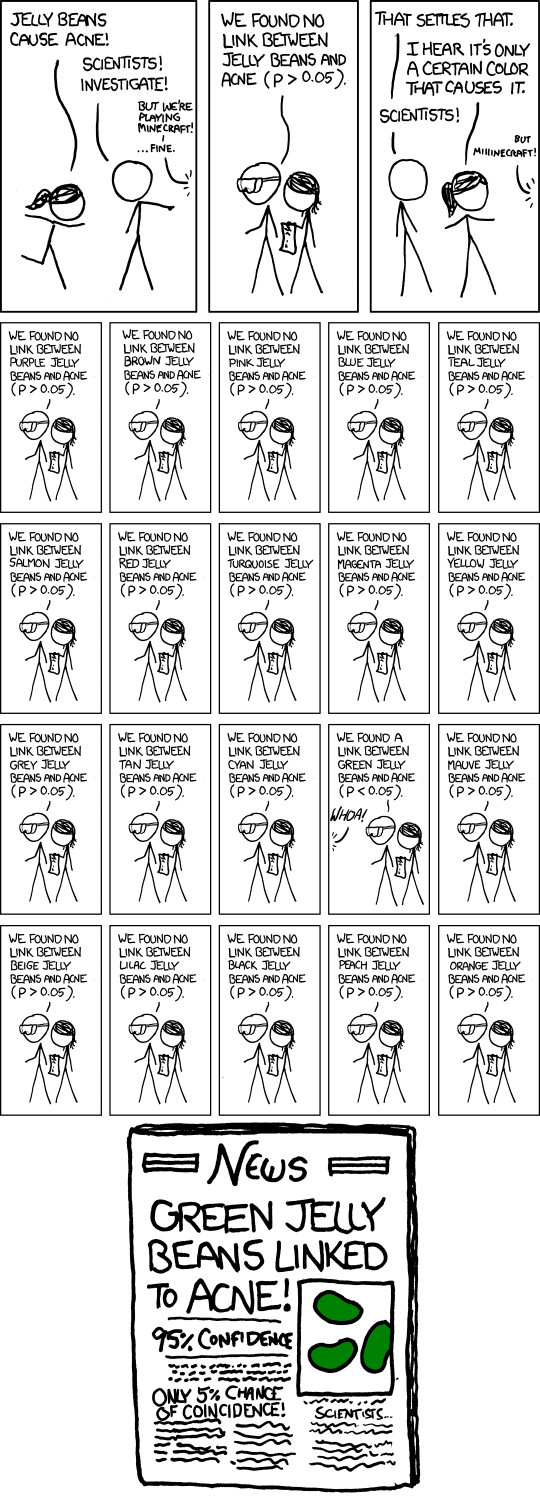

The problem with conducting multiple hypothesis tests is simple: if you test conduct 100 hypothesis tests at the 5% level, even if all of the null hypotheses are true you would expect to reject around 5 hypotheses. This isn’t necessarily an issue if you keep in mind that you should expect to see around 5 rejections, but it definitely is a problem if you go cherry picking for results like this…

There are two main approaches to dealing with this problem. I’ll first talk about the most obvious way to deal with it which is to reduce the number of tests by aggregating your outcome variables. Next, I’ll talk about an alternate approach which instead adjusts the p-values of each test to account for the multiple testing. In addition to these two main approaches to the problem, I’ll also talk about my favorite approach: ignoring the problem. (But we warned, you can only get away with this under certain conditions! Read below for more.)

Approach 1 - Reduce the number of tests

The most straightforward approach to dealing with the problem of multiple hypothesis tests is to reduce the number of tests by aggregating your outcome variables into an index. In principle, you could aggregate your outcome variables into a single index however you wanted but some ways make more sense than others. For example, it probably isn’t a good idea to take a simple average of different outcomes because the relative weighting of each variable would depend greatly on the scale on which each variable is measured.

The approach Anderson uses is as follows:

- Normalize each outcome variable by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation of the control group. In symbols, calculate:

$$\tilde{y}{ik}=\frac{y{ik}-\bar{y}k}{\sigma{k,c}}$$

Where i indexes observations and k indexes outcomes.

- Calculate \( \hat{\Sigma} \), the sample variance covariance matrix for this vector of transformed outcomes

- Calculate \( \mathbf{s_i}=\hat{\Sigma}^{-1}\cdot \mathbf{\tilde{y_i}} \) the dot product of the inverse of the sample variance covariance matrix and the vector of outcomes for each observation

- Add up the elements of \( \mathbf{s_i} \) to get your final index

Unfortunately, I am unable to find code in Stata to do this. Here is some sample code showing how to do this in Python. If anyone finds / writes code to do this, please let the rest of us know.

Anderson’s approach seems like a good approach if there is no alternative principled way to aggregate the outcome variables. As Anderson points out, this approach increases power by weighting those outcome variables that are not highly correlated with other outcome variables more. In some cases there might be a more natural theory based way of aggregating the outcome variables. For example, if you think the various outcome variables all measure some latent variable you might use item response theory or something else to estimate the latent variable.

As a sidenote, as great way to test for balance at baseline in an RCT is to use randomization inference on a single index constructed using basically the same approach. See here for more info.

Approach 2 - Adjust your p-values

A second approach to dealing with multiple tests is to adjust your p-values to take into account the fact that you are conducting multiple tests at the same time. The typical way to do this is to control the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER), defined as the probability of making a single type 1 error (i.e. rejecting the null when the null is true). (This isn’t the only thing you could control for though. See here for an alternative.) The easiest, but most conservative, way to control the FWER is to simply multiply your p-values by the number of tests you are conducting. This method, called the Bonferroni method, works because the probability of making any type 1 error can’t be larger than the sum of the probabilities of making a type 1 error when all the nulls are true. Due to its simplicity, the Bonferonni method is useful for performing power calculations.

The Bonferroni method works, but, as I mentioned, it’s really conservative. There a couple of ways we can do better: by using a step-down method and by taking into account the correlation between test statistics. Step down is a nifty trick in which you first order p-values smallest to largest and then sequentially reject null hypotheses using the smallest p-value first until you encounter a p-value that is too large after which you fail to reject all further hypotheses. This page has a good explanation of why this works for the step down equivalent of the Bonferroni method, the Holm-Bonferroni.

The other way you can get more power is by taking into account the correlation between test statistics. The basic idea here is that if your test statistics are all perfectly correlated you shouldn’t be adjusting your p-values at all because you should either reject all of the hypotheses or fail to reject all of them.

Anderson uses a combination of these two tools to increase the power. If you want more details of the intuition behind this technique, I found this article helpful.

Again, we were unable to find code in Stata to do this. If anyone has any suggestions, please let us know.

Approach 3 - Ignore the problem (see disclaimer below)

Now we come to my personal favorite approach – ignoring the problem. But first, I should offer a strong disclaimer: this is only a reasonable option in certain circumstances. To see why you sometimes might want to ignore the multiple hypothesis testing problem, consider a situation in which you happen to run 10 completely independent RCTs for a single client at the same time which eack look at completely different interventions targeting different outcomes. In this case, you almost certainly wouldn’t want to correct the p-value for one RCT to take into account the fact that you happen to be running another RCT at the same time. Often the decision of whether one should correct for multiple hypothesis testing or not is subtle and depends on your perspective. I don’t want to go into the full debate here, but I think that a useful approach for determining whether ignoring the problem is to first answer the following two questions. First, are each of the hypothesis tests informing a separate independent decision or are they informing a single decision? For example, is the purpose of the hypothesis tests to determine whether to individually continue each of ten programs or is the purpose to determine whether any of the ten programs? Second, will the results from the evaluation be shared with the outside world or just with the client? If the answer to the first question is “independent decisions” and the answer to the second is “just the client,” you might consider ignoring the problem. (But make sure to run this by your TT point person first!)